For these children, education begins not as a bridge to knowledge, but as a barrier to it. But what if we reversed that? What if children were initially taught in the language they speak, sing, and dream in—the language of their stories, songs, and everyday life? Welcome to the transformative potential of Mother-Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE)—a globally recognised development strategy that not only improves learning outcomes but also empowers children, involves families, and nurtures cultural identity. The psychological toll of language barriers in school is substantial. For many children, entering a classroom where the medium of instruction is foreign can be psychologically overwhelming.

For these children, education begins not as a bridge to knowledge, but as a barrier to it. But what if we reversed that? What if children were initially taught in the language they speak, sing, and dream in—the language of their stories, songs, and everyday life? Welcome to the transformative potential of Mother-Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE)—a globally recognised development strategy that not only improves learning outcomes but also empowers children, involves families, and nurtures cultural identity. The psychological toll of language barriers in school is substantial. For many children, entering a classroom where the medium of instruction is foreign can be psychologically overwhelming. Imagine being five years old and eager to learn. You sit down, pencil in hand, only to realise you cannot understand what your teacher is saying. You may find it hard to ask questions, request help, or even let someone know you need the bathroom. Now imagine this happening every day. Instead of sparking curiosity, school can become a source of anxiety and alienation.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Key Psychological Effects:

- Fear, Anxiety, and Withdrawal

- Children surrounded by an unfamiliar language often experience performance anxiety, social withdrawal, and low motivation. According to Cummins (2001), these children may enter “silent periods” in class, during which they remain nonverbal for weeks or months.

- Low Self-Esteem and Identity Conflict

- When a child’s language is ignored or devalued, it sends a message that their identity is not welcome in school. They may feel ashamed of their language, try to “fit in” by rejecting it, and begin to see themselves as “less intelligent” than their peers.

Example: In Francophone Africa, children who speak Wolof or Lingala are often labelled “slow learners” because they cannot yet respond in French, even though their cognitive abilities are on par with those of their peers.

- Delayed Cognitive Development

- Learning in an unfamiliar language places an additional burden on working memory, which in turn reduces focus on the content. A South African study (Heugh, 2002) found that students taught early in English performed worse across subjects than those initially taught in their native language.

- Disconnection from Family and Culture

- When schools reject local languages, children can grow distant from their culture and family traditions. Parents often feel excluded, and intergenerational learning suffers as a result.

Case in Point: In Southeast Asia, minority children often lose fluency in their mother tongue by adolescence due to exclusive instruction in national languages—cutting them off from elders and oral heritage.

Why Mother Tongue Matters for Development

Now, let us flip the story.

When children start school in a language they understand, they are more confident, more engaged, and more successful. Learning becomes a process of building on what they already know—rather than struggling to decode unfamiliar words.

According to global research:

- UNESCO (2022): Children taught in their mother tongue are more likely to succeed in reading, writing, and math.

- World Bank (2021): Reading outcomes improve 2–3 times faster in first-language settings.

- Long-term Benefit: Early mother-tongue instruction leads to more substantial second-language acquisition in later years.

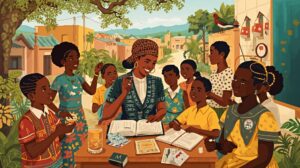

The Role of Parents and Communities: The Heartbeat of Learning

One of the most overlooked advantages of mother-tongue education is its capacity to engage families and communities as vital stakeholders in the learning process.

Parents Become Active Learning Partners

When schools speak the same language as homes:

- Parents—especially those with limited formal education—can help with homework.

- Grandparents become educators, sharing folktales, songs, and proverbs with their grandchildren.

- Families engage more in school events and decision-making.

In Nepal, when MTB-MLE programs were introduced in Tharu and Tamang-speaking areas, parents who had never attended school began reading with their children—and even requested adult literacy classes themselves (Save the Children, 2016).

Communities Shape Curriculum and Classroom Content

Community members—elders, artisans, farmers, and healers—become curriculum contributors, helping create lessons that reflect real lives and local wisdom.

- Oral traditions become storybooks.

- Traditional practices are included in science and health lessons.

- Teachers co-create culturally relevant materials with input from the local community.

In Papua New Guinea, local communities helped map out knowledge—from medicinal plants to fishing strategies—which were then integrated into classroom materials.

In Ghana, the Ghana Institute of Linguistics, Literacy, and Bible Translation (GILLBT) collaborates with communities to develop educational resources in over a dozen local languages.

Community-Driven Educational Planning

MTB-MLE turns education planning from a top-down process into a collaborative community effort.

Communities help with:

Role Example

Language Mapping: Identifying which languages are spoken in which areas.

Teacher Recruitment: Nominating local bilingual candidates for training.

School Governance Participating in curriculum review and development plans.

Policy Feedback Advocating for inclusive and responsive language policies.

“When we speak our language at school, we are not just learning—we are belonging.”

— Parent, Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Global Examples: Mother Tongue Meets Community Power

Bangladesh: Community-Created Curriculum

- In the Chittagong Hill Tracts, tribal communities collaborated with NGOs to develop textbooks, share folk stories, and train local teachers.

- Impact: Early-grade reading scores improved, and parents started trusting the school system again (UNESCO Asia-Pacific, 2019).

Ethiopia: Grassroots Advocacy

- In Ethiopia, regional education bureaux consult communities when selecting languages for instruction. Parents in Somali and Sidama formed language committees to demand teacher training and materials in their local languages.

- Philippines: Schools by the People

- Since 2012, the Philippines’ MTB-MLE policy has depended on community participation to:

- Identify school district languages

- Create storybooks and resources

- Organise reading festivals and cultural events

- Fun Fact: Each August, “Buwan ng Wika” (Language Month) celebrates Filipino and local languages through performances, storytelling, and poetry.

Cultural Benefits Beyond the Classroom

Mother-tongue education does more than improve test scores.

- It also:

- Revitalises endangered languages

- Through their use in schools, the younger generations help keep them alive.

- Bridges generations

- Elders become part of the learning process, reinforcing values and heritage.

- Strengthens identity in a globalised world

- Children familiar with their culture tend to succeed as global citizens.

- Promotes social inclusion

- Respect for minority languages fosters cohesion and reduces marginalisation.

- What Is Holding Us Back?

- Despite the evidence, many countries still hesitate to implement MTB-MLE fully.

Common barriers include:

- Lack of materials in local languages

- Shortage of trained bilingual teachers

- Insufficient funding and political will

- Parental belief that English or French guarantees success

- Educational planning that excludes communities

What Can Be Done? (And Where You Come In)

- Here are concrete steps we can take to scale MTB-MLE successfully:

- 1. Start Locally, Scale Smartly

- 2. Pilot programmes in selected districts document their results and expand based on community feedback.

- 3. Train and Empower Local Teachers

- 4. Provide scholarships for bilingual youth to become teachers in their own communities, thereby fostering bilingual education and cultural diversity.

- 5. Co-Create Learning Materials

- 6. Collaborate with elders, artists, and linguists to develop textbooks, videos, and audio content in local languages, using smartphones for storytelling.

- 7. Engage Parents at Home

- 8. Use WhatsApp, radio, and SMS to share literacy tips, bedtime stories, and songs in local languages.

- 9. Advocate for Inclusive Policy Making

- 10. Push for policies that include community consultations, language mapping, and multilingual curricula to support inclusive education.

Final Word: Speak to Empower, Plan to Include

Education should never feel like a foreign language. When the language of school reflects the language of home, learning becomes a celebration of identity — not an erasure of it. It becomes a bridge between generations, cultures, and between tradition and progress. Mother-tongue instruction is more than just a teaching method — it is an innovative, inclusive, and sustainable approach to development. So, whether you are a policymaker, teacher, parent, or student, your voice matters. Let us ensure it is heard in the language that matters most.