Africa stands at a crossroads. The continent has a vibrant youth population, dynamic civil societies, and a deep well of indigenous democratic traditions — from village councils to consensus-based decision-making systems. Yet, unless these are elevated above elite-driven power struggles and formalistic governance, disempowerment will persist.

Africa stands at a crossroads. The continent has a vibrant youth population, dynamic civil societies, and a deep well of indigenous democratic traditions — from village councils to consensus-based decision-making systems. Yet, unless these are elevated above elite-driven power struggles and formalistic governance, disempowerment will persist.

Rebuilding democracy in Africa means:

Putting people before parties,

Prioritising policies over patronage,

And ensuring that the ballot translates into better lives.

Only then can democracy fulfil its true purpose — as a vehicle for dignity, justice, and inclusive development.

This article explores the crisis of democracy in Africa through the lens of youth disempowerment, cultural alienation, and systemic exclusion. Despite the continent’s youthful population and post-independence aspirations, democratic systems have often failed to deliver inclusive governance. The piece highlights how electoral authoritarianism, elite capture, and economic marginalisation silence youth voices while eroding traditional governance models. Drawing on real-life narratives, scholarly insights, and case studies—such as #EndSARS and #FeesMustFall—the article illustrates both the barriers and possibilities for transformative change. It proposes a reimagined model of “Afro-democracy,” grounded in African traditions, communal leadership, and youth agency, and offers a culturally relevant, participatory framework for the continent’s democratic future.

A Generation in Waiting

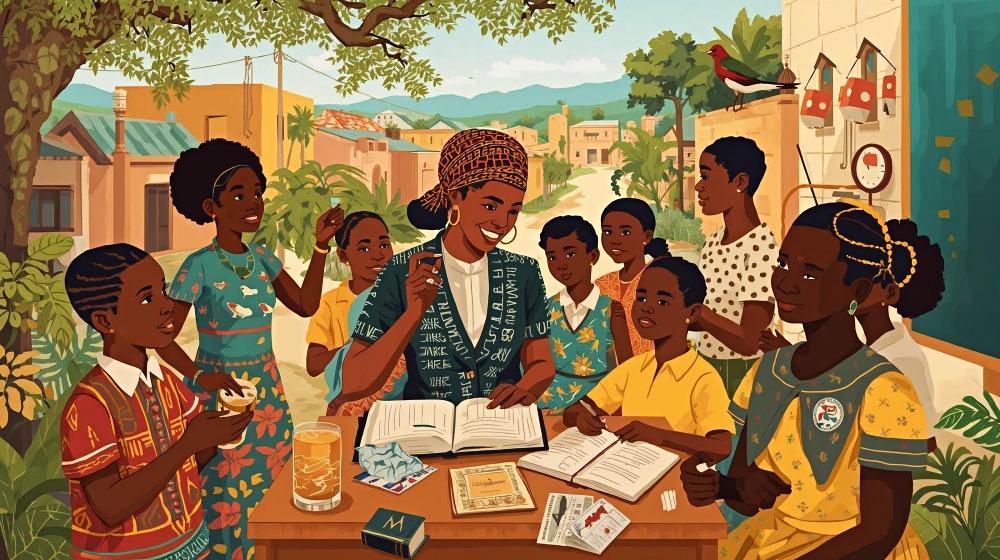

Amina, a 22-year-old fruit seller and law student in Kampala, Uganda, represents the aspirations of many young Africans. Every day, she balances her studies with long hours at the market, where she is forced to sell fruit to pay for her tuition and support her family. Despite her dedication, Amina faces the stark reality of political exclusion and cultural alienation that haunts many of her peers. Her legal aspirations are tempered by the knowledge that nearly two-thirds of young workers in Uganda, like her, struggle to find stable employment. This personal conflict illuminates the broader systemic hurdles faced by African youth and underscores the urgent need for transformative change across the continent.

Although democracy is often celebrated in Africa, its implementation frequently falls short. For many, especially young people, democracy remains an unfulfilled promise. The principles of self-governance and equal participation are often overlooked, resulting in the exclusion of young Africans from meaningful political and social engagement.

This article examines the core crisis facing democracy in Africa, focusing on youth marginalisation and the erosion of cultural identity. How can African youth turn protest into lasting power? The article addresses this question and is structured in three parts: identifying the root causes of youth marginalisation, assessing the impact of cultural disconnection on political engagement, and exploring how youth and cultural traditions can help build a more inclusive democratic future. Drawing on narratives, empirical research, and case studies, the article highlights both challenges and opportunities for transformative change.

The Democratic Illusion in Africa

Following independence, Africa experienced widespread optimism. The end of colonial rule generated expectations of self-governance, dignity, and substantive progress. However, this optimism diminished rapidly. By the 1970s, the prevalence of coups, military dictatorships, and authoritarian regimes undermined aspirations for genuine democracy.

In the 1990s, Africa saw renewed democratisation, with multi-party elections raising hopes for greater freedom and representation. However, these reforms were often superficial. Power largely remained with established elites, who manipulated laws and suppressed dissent to retain control. In contrast, Ghana has shown that genuine democratic transformation is possible. Since 2000, Ghana has experienced peaceful transitions of power through seven consecutive national elections, illustrating that strong institutions and committed leadership can overcome entrenched elite dominance. To highlight Ghana’s success, it is essential to note that, across Africa, many countries have experienced frequent coups and unstable power transitions. For instance, between 2000 and 2020, the continent experienced approximately 20 coups, in stark contrast to Ghana’s steady democratic progress.

This pattern is evident in numerous African countries. In Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe’s rule from 1980 to 2017 maintained a democratic façade while operating autocratically. In Nigeria, persistent voter apathy and election rigging frequently exclude young people from the political process. In Sudan, despite the removal of Omar al-Bashir, the military continues to dominate politics, impeding the establishment of genuine democracy.

Ultimately, these dynamics have produced what is often termed ‘electoral authoritarianism.’ In this context, democratic institutions exist in form but lack substantive democratic values and practices. Electoral authoritarianism can be understood through two primary diagnostics: media capture and judicial co-optation. Media capture refers to a situation where governmental elites control significant portions of the media, thereby manipulating public perception and obstructing dissent. This is distinct from standard state media ownership in that it systematically eliminates independent voices and restricts the free flow of information. For instance, consider a popular radio station in Zimbabwe that once aired a segment critical of government policies. The segment was abruptly cut off mid-broadcast, and the station was later pressured to air only content approved by government officials, effectively silencing dissent and shaping public perception in accordance with elite interests. Judicial co-optation involves manipulating judicial institutions to legitimise the actions of those in power, often undermining the rule of law. However, some scholars argue that, in specific contexts, judicial institutions and segments of the media have at times served as checks on executive power or provided limited spaces for dissent, thereby illustrating occasional resistance to elite control. Nonetheless, democracy in Africa frequently serves as a facade, with the ideals of self-governance and equal participation remaining unattainable, particularly for young people.

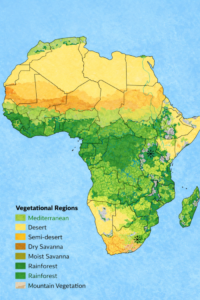

Democracy is closely tied to culture. Colonialism in Africa disrupted indigenous governance, replacing community-based systems with Western models that often proved incompatible. This shift marginalised traditional practices and introduced majority-rule politics, creating a disconnect between formal government and daily life.

This disruption led to widespread cultural alienation. Educational systems often marginalise indigenous knowledge in favour of Western curricula. Local languages were replaced by colonial languages in schools and public life, while the media promoted foreign lifestyles and portrayed African identity negatively.

These transformations have had significant consequences. Many young Africans now experience a sense of disconnection from their cultural heritage and uncertainty regarding their societal roles. In the absence of a robust cultural foundation, civic engagement is often interpreted through a Western lens, which may not align with local realities. Although traditional leaders retain influence in rural areas, they have largely been excluded from formal political processes. This ongoing tension between modernity and indigenous practices contributes to feelings of alienation and disempowerment among youth. Consider the case of Kiara, a 28-year-old urban professional in Nairobi, who struggles to preserve her native language, Luo, in a city where English is the predominant language. This linguistic shift encapsulates the cultural alienation experienced by many young Africans, as their mother tongues, symbols of identity and tradition, gradually fade in urban environments. Kiara’s struggle affects her ability to engage fully in civic discourse, as the loss of her native language also entails the loss of the cultural and contextual nuances embedded in it. This loss can lead to misunderstandings or a lack of engagement with policy debates important to her community, which are conducted in a language and framework that may seem foreign to her. This highlights the practical impact of cultural and linguistic erosion on democracy, as it limits effective participation and understanding among young Africans such as Kiara, thereby diminishing their potential contributions to societal development.

The Youth Factor: Africa’s Sleeping Giant

Africa is the world’s youngest continent, with over 60% of its population under 25 (Stone, M. 2020, May 22). This demographic profile offers a potential demographic dividend, yet Africa faces significant challenges in harnessing this advantage.

Systemic Underrepresentation

Despite their significant numbers, young Africans are still underrepresented in formal political institutions. The average age of national leaders exceeds 62, whereas the median age of the population is 19, highlighting a significant intergenerational gap. To put this into perspective, there is approximately one lawmaker over 60 for every three citizens under 30, making the generational gulf instantly graspable. As a result, youth perspectives and needs are often overlooked in policymaking. Systemic barriers, including inadequate education systems, limited access to capital, and insufficient policy support for youth-led enterprises, contribute to widespread youth unemployment. Rather than recognising youth as valuable contributors to societal progress, policymakers and elites frequently label them as potential sources of unrest, particularly during elections and protests. However, this stereotype of youth as a threat is not entirely accurate. A recent survey revealed that a significant majority of young Africans prefer to engage in policy influence rather than protest, viewing themselves as allies in societal development rather than risks. This finding underscores the need to reframe youth as partners in progress, challenging the perception that they are primarily a disruptive force. This perception not only overlooks the structural factors underlying youth unemployment but also further marginalises young people and heightens their sense of exclusion.

Demanding Change: Youth Movements

Despite these challenges, African youth remain active and outspoken. Movements such as #EndSARS in Nigeria and #FeesMustFall in South Africa demonstrate how young people are leading digital, decentralised, and confrontational forms of democratic engagement (24Hip-Hop, 2; UNDP, 2021). #EndSARS led to the disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad in Nigeria (Freedom House, 2023), while #FeesMustFall prompted South African universities to freeze tuition fees (EISA, 2022). Other movements, such as Y’en a Marre in Senegal and Le Balai Citoyen in Burkina Faso, have also mobilised youth for democratic accountability (UNDP, 2021). However, many young Africans still feel marginalised within current political systems. Without formal participation mechanisms, their influence remains mostly informal or grassroots (Kalina, 2017). Without meaningful reforms to include youth in governance, Africa risks losing its most valuable resource. Additionally, ongoing economic crises in many countries hinder citizens’ ability to participate in democratic processes, as basic needs remain unmet (African Union, 2020).

Lessons from Youth Movements

– #EndSARS (Tactic: Digital mobilisation against police brutality. Result: Disbandment of the SARS unit, increased awareness of police reform needs.)

– #FeesMustFall (Tactic: University protests focusing on tuition fees. Result: Freeze on tuition fees, sparked national dialogue on education affordability.)

– Y’en a Marre (Tactic: Creative engagement through music and activism. Result: Youth voter mobilisation, increased political accountability.)

– Le Balai Citoyen (Tactic: Grassroots activism and political engagement. Result: Successful nonviolent ousting of a long-time president.)

- Unemployment leaves millions dependent and disillusioned, making it harder for African youth to engage in democracy. Corruption erodes trust in public institutions, while inequality fuels resentment and causes many to withdraw from civic life, compounding the effects of unemployment and corruption on democratic participation.

- Corruption erodes trust in public institutions.

- Inequality fuels resentment and causes many to withdraw from civic life, compounding the effects of unemployment and corruption on democratic participation.

Case Studies

- In Tunisia, youth-led economic grievances sparked the Arab Spring.

- In Senegal, high youth unemployment drives migration and protests.

- In Kenya, economic hardship among youth leads to both political apathy and vulnerability to manipulation.

Economic disempowerment fosters political disengagement by reducing individuals’ belief in the efficacy of political participation. When citizens repeatedly experience that voting does not result in tangible improvements in their livelihoods and that entrenched elites maintain power regardless of electoral outcomes, a sense of helplessness and disillusionment develops. This perceived lack of agency diminishes motivation to participate in civic life. Empirical studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between high unemployment rates and low voter turnout, indicating that economic hardship erodes individuals’ sense of investment in political processes. For example, a 2021 survey found that in regions where unemployment rates exceeded 25 per cent, voter turnout dropped by nearly 10 per cent compared to more economically stable areas. However, a thought-provoking question emerges: What single factor transforms economic grievances from withdrawal to activism? The answer often lies in the trust and solidarity found within peer networks. Nevertheless, economic disempowerment can also generate a sense of urgency and collective grievance that catalyses political engagement. In such cases, youth and civil society groups translate their frustration into activism and mass mobilisation, using protest and collective action to contest exclusion and demand change. This dynamic underscores how economic marginalisation, while often dampening democratic participation by undermining confidence in institutional efficacy, can, under certain conditions, activate new forms of political engagement aimed at challenging the status quo. As discussed in the following section, these patterns of political apathy and episodic mobilisation are central to understanding the ongoing barriers and opportunities for youth participation in Africa’s evolving democratic landscape.

Economic Disempowerment and Political Apathy

It is often said that democracy cannot be discussed with those who are hungry, a reality in many African nations. Ongoing economic crises are significant barriers to democratic participation and undermine civic engagement.

Unemployment remains widespread, leaving millions, especially youth, in precarious situations. This lack of stable livelihoods breeds dependency and widespread disillusionment with political processes.

Corruption compounds these challenges by eroding trust in public institutions. For example, in Nigeria, reports of government officials misappropriating public funds have repeatedly surfaced, leading to widespread public outcry and scepticism regarding official accountability when citizens observe public offices serving private interests, such as through embezzlement or preferential contracts. Their faith in governance declines, making genuine democratic participation more difficult.

Inequality fuels resentment and causes many to withdraw from civic life. The widening gap between the privileged and the majority increases frustration and discourages political engagement.

Case Studies

- Tunisia: Youth economic grievances sparked the Arab Spring, demonstrating how hardship can drive major movements for change.

- Senegal: High youth unemployment has led to increased migration and frequent protests, as young people seek better opportunities and express their discontent.

- Kenya: Economic hardship among youth has resulted in political apathy and increased vulnerability to elite manipulation.

Economic hardship often leads to widespread political apathy. When citizens believe voting offers no real benefits and mainly serves the powerful, public engagement declines, and the promise of democracy fades. However, economic struggles can also motivate collective action, as seen in Tunisia’s Arab Spring, where youth grievances led to mass mobilisation and demands for change. This shows that while hardship often causes disillusionment, it can also spark renewed activism and participation under certain conditions.

Democracy as Theatre: Who Really Holds Power?

In many African countries, the democratic process often appears staged, with election outcomes seemingly predetermined. Real power lies not in visible institutions but in informal networks of political elites, military figures, and foreign interests. A concrete illustration of this is seen in the tacit alliances between military contractors and political parties. A military contractor might funnel money and equipment to a political party in exchange for favourable policies or contracts. This flow of resources begins with funding key political events or campaigns, where military contractors provide logistical support or financial backing. In return, once the party gains power, these contractors are rewarded with lucrative government contracts or policy relaxations that benefit their operations. Such a transaction chain illustrates how military and corporate entities effectively pull the strings backstage, ensuring the political landscape remains favourable to them. These alliances conceal the underlying machinery behind what appears to be democratic processes, giving the public only an illusion of choice.

Elite capture is a central factor sustaining this pseudo-democratic environment. A small, privileged group controls resources and policymaking, ensuring outcomes that serve their interests. This concentration of power marginalises the broader population and limits genuine public participation. Africa reveals distinct differences and intervention points between entrenched civilian oligarchies and coup-prone military elites. Civilian elites, often tied to long-standing political dynasties or business interests, maintain control through economic leverage and institutional manipulation. Meanwhile, military elites in countries such as Guinea, Mali, and Burkina Faso have historically interfered directly in politics, overturning civilian rule through coups to reset political landscapes to their advantage. Each group poses unique challenges and requires tailored responses to foster genuine democracy.

Foreign involvement further complicates the political landscape. France maintains a military presence, while China’s economic influence is expanding. These external powers often pursue their own interests, sometimes at the expense of local needs and national sovereignty.

Disinformation campaigns and state-controlled media further complicate these dynamics. Misinformation misleads voters, discourages civic activism, and fosters division. For example, a widely circulated rumour suggested that a political party used witch doctors to influence elections, playing into existing stereotypes and fears about traditional practices. This rumour not only exploited cultural symbols but also deepened mistrust in the democratic process. As a result, citizens question the integrity of the democratic process and the reliability of information. This demonstrates why media literacy that is grounded in local culture is pivotal, helping individuals discern fact from fiction in ways that resonate with their lived experiences and cultural understandings.

As a result, democracy in these contexts often sacrifices substance for spectacle, with real centres of power hidden behind a theatrical façade.

- All Posts

- Culture and Development

- Democratisation

- Diversity and Democracy

- Language versus Education

- Leadership

- Social Psychology

- Traditional versus Foreign Social Construct

- Upper Guinea and West Africa

In classrooms around the world, many children are greeted on their first day of school not with excitement, but with

Africa stands at a crossroads. The continent has a vibrant youth population, dynamic civil societies, and a deep well of

Cultural Renaissance: A Path to Re-empowerment

Africa is undergoing a cultural renaissance, signalling a shift in power and identity. Young Africans are leading this revival, reclaiming heritage and redefining power in their communities. Through music, artists convey political messages, offer social commentary, and mobilise listeners, inspiring dialogue and empowering youth political engagement. A striking example of this impact is Falz’s song ‘This is Nigeria,’ which uses popular music to critique socioeconomic issues and governance, sparking significant national conversations and media coverage. The song’s release contributed to increased voter awareness, with reports indicating a noticeable spike in youth voter registration following its release. These changes demonstrate music’s ability to transcend entertainment and drive tangible civic impact by engaging the youth to participate actively in elections and policy debates.

Fashion as Resistance

The revival of local textiles, traditional hairstyles, and indigenous fashion symbolises resistance and pride. By embracing African aesthetics, young people challenge global trends and assert cultural identity. Fashion becomes an act of agency and resilience.

Literature and Film: Reclaiming Narratives

African writers and filmmakers are increasingly producing works that centre African experiences and realities. Their creative output challenges colonial narratives and offers authentic perspectives. Through literature and film, they reshape perceptions of the continent and amplify African voices. This culturally grounded movement has sparked scholarly debate on whether African expression should focus mainly on reclaiming indigenous languages and traditions (Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o) or also embrace global influences and hybrid identities (Achille Mbembe). Others, such as Barber (2007), caution that emphasising dominant indigenous narratives may exclude minority perspectives. Despite these complexities, supporters of curriculum decolonisation agree that integrating local knowledge fosters resilience and identity among African youth (Chati, 2020). Thus, while cultural re-empowerment is seen as essential for inclusive development, the challenge lies in balancing traditional heritage with contemporary global realities.

From Protest to Power: Youth Redefining Democracy

Young Africans are driving tangible change in their communities and nations. By using smartphones, social media, and civic technology, they are finding new ways to engage politically and to empower themselves.

Platforms such as BudgIT in Nigeria and Mzalendo in Kenya have improved transparency and made government budgets and legislation more accessible. BudgIT, for example, has simplified complex fiscal information for the public, prompting debate and some government action (UNDP, 2021). Beyond information access, civic technology fosters accountability and allows youth and other marginalised groups to participate more actively in governance. Although issues like limited digital access and government censorship persist, these technologies have helped shift many citizens from passive observers to engaged participants. They also enable youth activists to organise and respond quickly, often bypassing traditional media.

Youth participation in local governance is rising, with young people organising at the community level to address needs and lead grassroots initiatives. Despite challenges such as intimidation, restrictive laws, and limited resources, a new generation of youth leaders is emerging, shifting from protest to proactive leadership.

Africa’s youth are moving from protest to positions of influence, demonstrating resilience and determination as they redefine democratic participation in ways that align with their priorities.

Reimagining Democracy for Africa

Africa is at a crossroads where imitating Western democracy is no longer enough. A bold, homegrown vision of Afro-democracy is needed, rooted in African cultures, traditions, and community structures. A metaphor to illustrate Afro-democracy might be “the village palaver under a digital tree,” signifying a blend of tradition with modernity. This model of governance prioritises cultural authenticity and emphasises communal bonds and lived experiences in decision-making processes (Gyekye, 1997). Unlike Western models, which often emphasise individualism and institutional structures, Afro-democracy embraces collective values and traditions rooted in indigenous practices and communal leadership (Gyekye, 1997).

A contemporary example of Afro-democracy is evident in Ghana, where participatory governance combines formal democratic processes with local chieftaincy institutions, thereby integrating traditional authorities into community-level decision-making. However, scholars have raised critiques of Afro-democracy, noting that focusing on indigenous traditions and communal leadership may risk entrenching existing social hierarchies or excluding minority voices if not carefully adapted. For instance, some argue that traditional systems can perpetuate gender or age-based inequalities, challenging the inclusivity that democratic governance aspires to achieve.

Given the continent’s youthful demographics, engaging young people is not only a matter of fairness but also a practical necessity for building dynamic, responsive democratic systems (African Union, 2020). By explicitly centring youth agency, Afro-democracy aims to transform governance structures so that young Africans move from the margins to the forefront of decision-making. In doing so, it seeks to address challenges of exclusion and capitalise on the creativity, activism, and leadership of youth, as demonstrated by youth-led initiatives and civic engagement across the continent (UNDP, 2021).

Afro-democracy values oral traditions, the wisdom of elders, and collective decision-making. These practices support problem-solving, guide communities, and preserve cultural heritage, fostering a more inclusive and locally grounded democracy.

Economic systems must also change. Afro-democracy promotes self-reliance and dignity, encourages locally driven solutions for sustainable employment, and reduces vulnerability to external pressures.

Genuine decolonisation of democracy in Africa requires more than political reform. It demands transforming culture, economic structures, and mindsets to create a system that authentically represents all citizens.

References

24Hip-Hop. (2023, August 17). Lazaris The Top Don: Leading a new wave of authentic hip-hop with ‘The Life of a Don Vol. 1’. https://24hip-hop.com/lazaris-the-top-don-leading-a-new-wave-of-authentic-hip-hop-with-the-life-of-a-don-vol-1/

African Union. (2020). Africa’s youth: The demographic dividend.

Chati. (2020). Strategies for virtual team building. https://chati.com/strategies-for-virtual-team-building/

EISA. (2022). Electoral trends in Africa.

Freedom House. (2023). Freedom in the World – Sub-Saharan Africa.

Gyekye, K. (1997). Tradition and modernity: Philosophical reflections on the African experience. Oxford University Press.

Stone, M. (2020, May 22). Brazil now 2nd to US in world in COVID cases. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/coronavirus-updates-covid-19-study-aims-vaccinate-10000/story?id=70824051

UNDP. (2021). Youth unemployment and political participation in Africa.